As part of my work with the National Science Foundation Small Business Innovation Research Program (SBIR), I recently organized an all-day Technology Commercialization Workshop at MIT. Later, during a follow-up speaking engagement, I focused on intellectual property strategy at the NSF SBIR Phase 2 conference in Baltimore.

There were two hundred Phase 2 SBIR grantee companies in attendance, each selected through a rigorous NSF review process that looks at technical merit and commercial potential. These high-potential companies seek to commercialize new technologies, and a $500,000 grant dispersed over the course of two years helps make that possible.

When speaking to innovators, I encourage them to make use of patent data in forming their technology commercialization strategies. There is no end to the amount of information and insight you can glean from analyzing the patent and technology landscape.

America is very much an anti-monopoly society, and yet the patent system grants a limited monopoly to inventors upon the grant of a patent. This is an important part of the American landscape—in fact, it appears in the Constitution itself. Without the ability to enjoy a limited monopoly, why would inventors feel the need to share their innovations with others?

The patent system increases our useful knowledge and helps propel our inventions and innovations. With each patent filed, we learn more about potential technology and ways to innovate, growing as a society with each and every invention. Without this ability to learn from and build upon others’ innovation, technology could never advance—or at least not at the rate we’ve enjoyed thus far.

The reality is that this knowledge has been difficult to practically access because of the detailed text-based nature of patents. Fortunately, data visualization technologies such as those used by IPVision has changed this.

Oil Fields and Medical Devices

One example I gave to the NSF SBIR Grantees comes from a project done by one of my MIT Sloan Fellow students in 2003. Sloan Fellows are sent by their companies to the MIT Sloan School of Management for an intensive one year MBA

This student from a South American oil field products and services company was considering a relatively new technology known as “expandable tubes.” It was thought these might cause a drastic change in the architecture of oil drilling and wells.

He wanted to investigate the patent landscape as part of his technology and opportunity assessment. He and his patent lawyer had identified four patents of interest to be investigated.

In 2003, the four patents, the “starting set,” were cited by nine other patents. Eight of them had titles that contained the words “oil field,” but one was a bit different: "removable gripping set screw.”

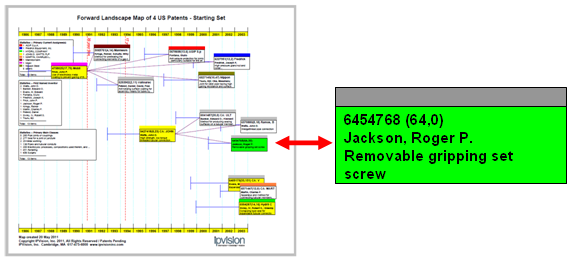

A forward patent landscape map of these four patents showed that this recently (as of then) issued patent had cited sixty-four other patents as prior art (shown as the "64" in the (64,0) label in the green patent box).

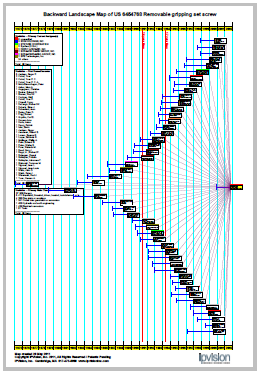

To identify these 64 patents we produced a backward citation map for this set screw patent. The map looks like this:

You can see the set screw patent at the right edge of the landscape. The patents fanned out to the left were named prior art. We noticed that most of these 64 prior art patents were medical device patents, specifically spinal-implant related.

The Advancement of Technology

The Sloan Fellow student found this quite exciting, because the technical issues involved in this oil field application and the medical device area were similar in many ways, although the environments are radically different. As the saying goes, "We are all victims of our own experience."

In his paper he stated, "[For this particular patent] most of the innovations fall within the medical equipment industry. This interesting characteristic of the IP landscaping techniques forces managers to do what is otherwise considered awkward and is often avoided: to look around and into different industries and study how their solution to problems could represent a possible alternative for innovations. In this case, the technology of well drilling and completion (oil and gas industry) tangentially contacts the medical equipment industry."

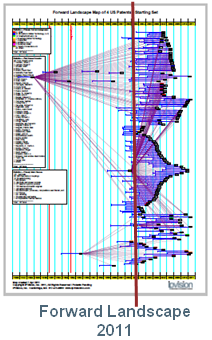

In using this example in my NSF presentation, I looked to see what had happened to the landscape of these four starting set patents since 2003. In 2003, there were nine forward citation patents citing the four starting set patents. Today there are 166.

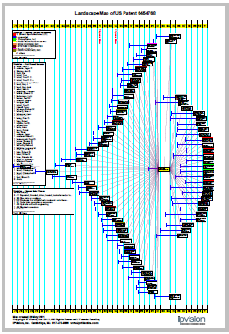

On the left below is what a landscape map looked liked in May 2011 (the red vertical line is 2003). The map on the right is the set screw landscape map showing the thirty patents that now cite this patent.

As the Sloan Fellow noted, "This systematic exercise provides the company with a powerful tool to constantly assess its position from a technological standpoint; gives direction of new technology development, avoiding further encroachment either by competitors or to competitors patents; and finally helps identifying opportunities for merging, acquisitions, alliances and license agreements."

Isn't this exactly what technology commercialization is all about? Based on the questions I received following my presentation, it is clear that these NSF SBIR innovators "get it."

Note: To see this and other papers on Intellectual Property Strategy go to patents.mit.edu.