With summer upon us, it’s a good time to get refreshed. Perhaps some water balloons? Make sure they’re Bunch O Balloons, who were ruled to have exclusive rights to their patent. But that should be obvious, shouldn’t it? We’ll help you decide.

Water Balloon Patent Case Overturned by District Jury

After a district jury from Texas awarded $12.3 million to the plaintiffs in the case involving two patents on devices to fill multiple water balloons, “Bunch O Balloons” owners Tinnus Enterprises brought against U.S. telemarketing company, Telebrand, a few points were made. First of all, even if the PTAB determines that your patent is invalid, as it did with Bunch O Balloons, a district court may disagree, and you could potentially still have a case. Because Telebrand had originally fought their case of patent infringement on obviousness, perhaps the jury felt there was nothing obvious in the design of water balloons. Therefore, unless you expect your water balloon (patent) fight to last four years like this one did, make sure you research design patents.

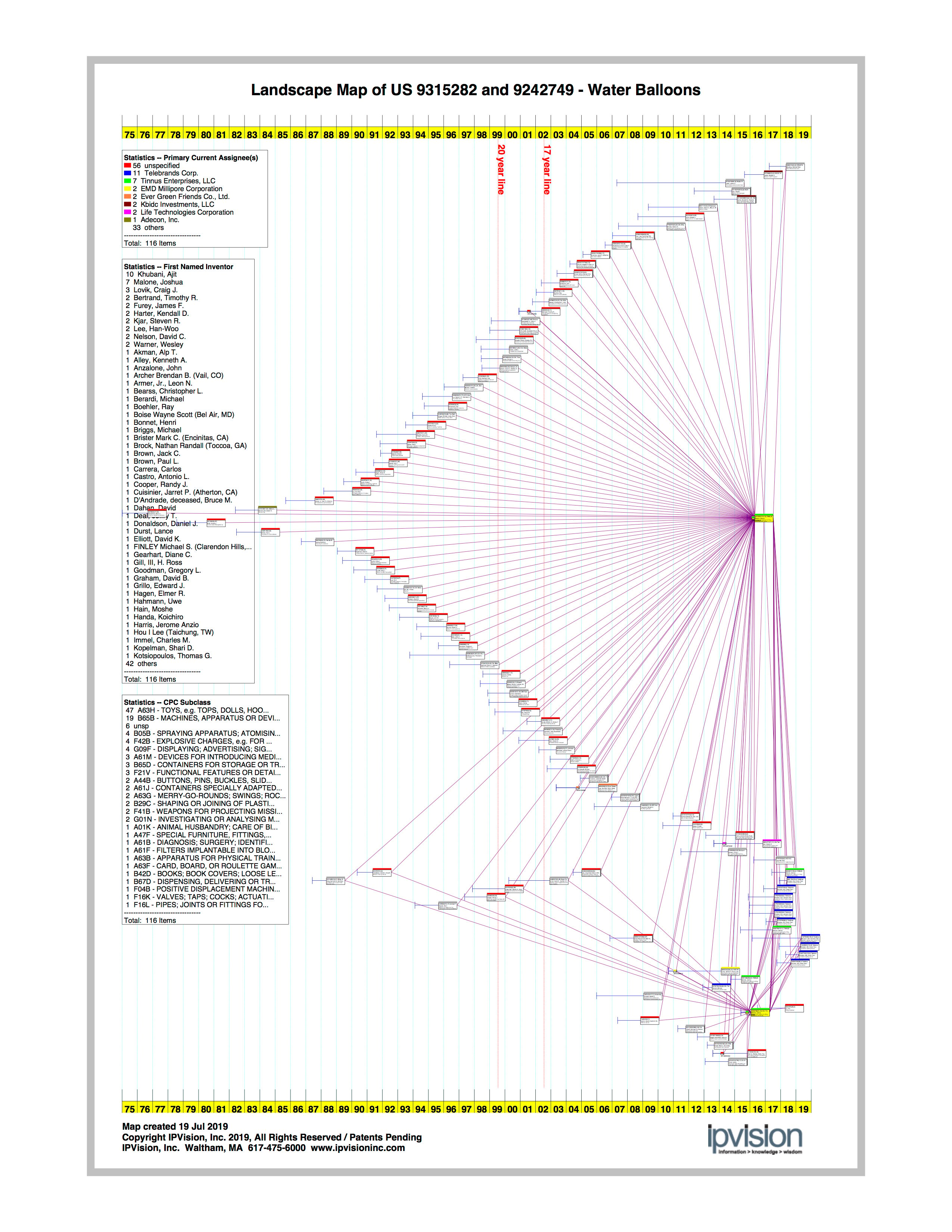

This is an IPVision Patent Landscape Map of the 2 patents in the Bunch O Balloons case. The 2 patents cite as prior art 91 other patents or published patent applications, 39 of which contain the word “balloon” in the title. Patented balloons are apparently not “novel.”

To learn how to read an IPVision Map, click here:

http://www.see-the-forest.com/help/general/patentmaps.php

When is Obviousness Actually A Legal Term?

Obviousness is not as obvious as a lay inventor may think. Because a patent application can be denied just on the basis of a term we use in everyday colloquial language, it’s essential to be sure you have the precise definition before filing to save yourself a denial, or worse, a lawsuit. So, to clear things up, here is the official legal definition: obviousness is when “the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art are such that the claimed invention as a whole would have been obvious before the effective filing date of the claimed invention to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which the claimed invention pertains.” (post-AIA statute, 35 USC § 103(a)) That clears it up, right? If it does not, just keep in mind that the key factor is proof. As with just about all legal verdicts, there needs to be proof to back up the determination.

Bob Langer, MIT’s prolific biomedical inventor, recounts his dealing with the Patent Office on the issue of obviousness of one of his early inventions of polymer systems that slowly and continuously release large molecule drugs:

“One of the challenges was getting a patent. In fact we filed a patent in 1976 and the Patent Office turned it down. I believe they turned it down five times between 1976 and 1981. My lawyer told me I should just give up, but I’ve never given up easily and I started to thinking about new ways in which we could get this patent allowed. The patent examiner said that what we had done was obvious, but I knew that wasn’t true since, as I mentioned, scientists saying it was impossible. So, I scoured the literature and I discovered that that there had been a paper published by five famous chemists and chemical engineers in 1979 that referred to our work by saying:

‘Generally the agent to be released is a relatively small molecule with a molecular weight no larger than a few hundred. One would not expect that macromolecules, e.g. proteins, could be released by such a technique because of their extremely small permeation rates through polymers. However, Folkman and Langer have reported some surprising results that clearly demonstrate the opposite.”—Stannett, Koros, Paul, Baker, Lonsdale, Adv. Poly. Sci., 1979.’

Is that a Patent or a Trademark?

Sports news recently reported that Tom Brady made a splash in the NFL offseason by trying to patent the nickname “Tom Terrific.” No one appreciate Brady’s adoption of the moniker—Brady himself confessed that he didn’t even like the nickname—and a tirade arose from angry New York Mets fans who wanted to protect their beloved Tom Seaver, who brought that name with him to the baseball Hall of Fame 50 years ago.

Brady reported that he only wanted to patent the name so that no one else could use it on him. Maybe he had good intentions, but he’d have been better off trying to trademark the name rather than patenting. Trademarks are words, phrases, images, colors, and/or sounds that associate in the mind of the consumer a particular source of goods.

Perhaps he did attempt a trademark, and the sports reporters were the ones who were confused. We may never know.

China is Number One in Number of Blockchain Patents

And the winner for the most number of blockchain patents filed from 2013 through 2018 is China. JD.com, China’s premier e-commerce company has filed for over 200 blockchain patents, just on their own. Competitor e-commerce giant, Alibaba, tops JD with the highest number of patents at 262, while two other Chinese internet companies are right behind.

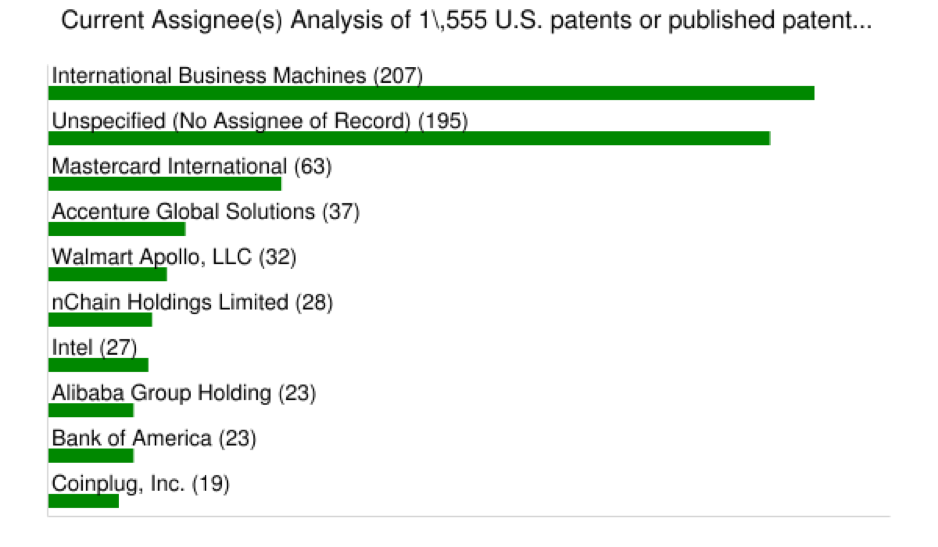

The U.S. is not far behind, as they occupy 21% of the global patent space, with 1,555 published applications or issued patents that contain the word “blockchain” in the title, abstract, or claims. In both cases, businesses are the most likely to file a patent (more than individuals or research companies), and do so 75% of the time, showing us just how important IP is in the financial market world.

The owners of “blockchain” patent properties in the U.S. are:

Need help discerning just how obvious your patent idea is? Or whether someone might be offended by the name you are trying to “patent”? Get in touch with IPVision for a consult today.