Understanding how efficient the Company is in generating and capturing inventions is one measure but boards of directors should be asking if the Company is patenting the right things, i.e., what is the Company’s intellectual property strategy?

Believe it or not, many Boards of Directors have zero insight into the intellectual property strategy of the company—or even knowledge of whether a strategy exists. Discover first if there is an IP strategy in place, and what that strategy consists of.

Development Strategy

Let’s think again about each of the patents applications that are generated as a result of your research and development activities. If we compare this to the Homestead Act of 1862, you may get an idea of what we mean.

During this time, people were given the opportunity to stake their claim in land across what is now the western United States. Settlers then had to file their claim in the local Land Office and then improve upon that property within the first five years of ownership. Only then could they file for a patent—yes, it was called a patent—also known as a title deed.

Without further development of the land, it became useless to the claimant. That’s the first takeaway here. Then, there is the claim strategy to consider. Should the claimant have simply rushed forward and claimed the first piece of land he or she could put a stake in, or was the wiser course of action to inspect the land they planned to claim to ensure it would support life upon it? Marshy or rocky land would prove useless without the ability to grow crops or nourish farm animals.

Beyond the quality of the land they claimed, they also should strategize the location of the land. Was it convenient to towns and thoroughfares? Was it adjacent to other land they had claimed—or perhaps adjacent to land claimed by their family? Could they access the land through easements or agreements with other landowners?

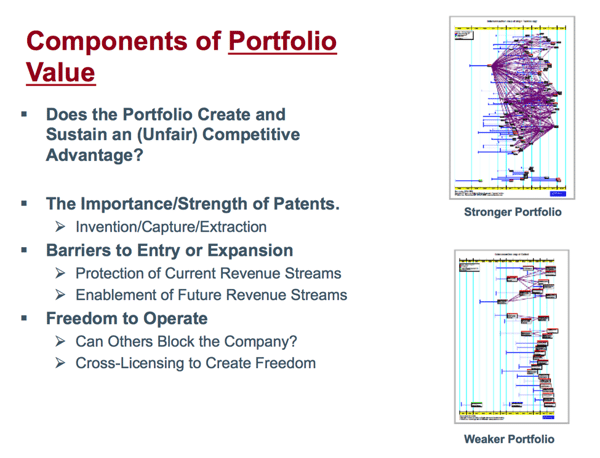

When we look at IPVision patent maps, we can see if companies had any strategy when staking their claims through patent applications. An interconnection map showing the cross citation of patents within a portfolio is the first place to start. When patents within that map don’t cite each other—aren’t adjacent properties that strengthen and quantify the land owned—they’re considered a weak portfolio. It’s indicative of Wild West style claims, where property was just grabbed without any sort of strategy in mind, and it can come back to haunt you.

Our Products, Our Patents, Our Competitors – Your Patent Rosetta Stone

In evaluating the company’s patent strategy, Boards of Directors also need a thorough understanding of the technology the company owns, how that technology is protected by patents, and—most importantly—which products were created with that technology. It’s not at all unusual for companies to allow patents to fall through the cracks—to have a very limited idea of the true amount of technology they actually own.

Can you imagine owning two adjacent pieces of land with no idea that those properties connect in some way? It’s possible if you weren’t responsible for purchasing the first piece of land and you haven’t maintained that land and the records well enough to have a full understanding of it.

For instance, imagine you know that you own technology for a vessel that can hold liquid. You are unaware that you also hold technology that provides insulative properties for that vessel, but you do know there’s a patent for a handle around here somewhere. Without the vessel, the handle is useless. Without the knowledge of the insulation capabilities, you have no clue that you’re holding all the technology necessary to make a coffee mug.

Tracing patents to the technology your company has developed isn’t as easy as it may sound, especially if some of your patents are older. You may have even missed out on chances to strengthen your portfolio and the patents within by citing technology you already own, simply because you didn’t realize you already owned it.

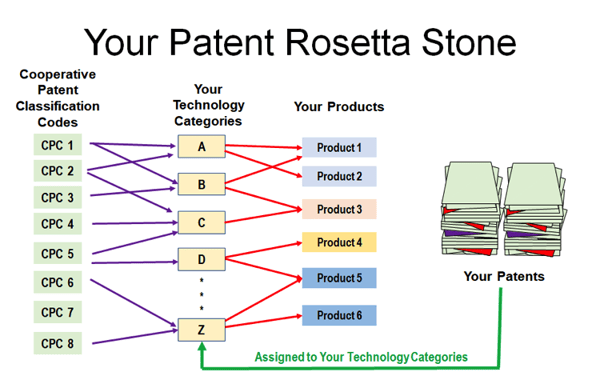

If you are going to map your patents to your products, which you definitely should, you should consider taking the next step and creating what we call a “Patent Rosetta Stone.” As you may recall, the original Rosetta Stone was inscribed with three versions of a decree issued in Memphis, Egypt in 196 BC. The decree had only minor differences between the three versions, which were in Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, Demotic script, and Ancient Greek, making the Rosetta Stone key to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs.

A Patent Rosetta Stone facilitates your understanding of the relationship of your products, technologies and patents. Once constructed, it can also be used to understand these relationships in your competitors’ portfolios, as well providing insights into potential emerging competitive threats and opportunities.

How to Create a Patent Rosetta Stone

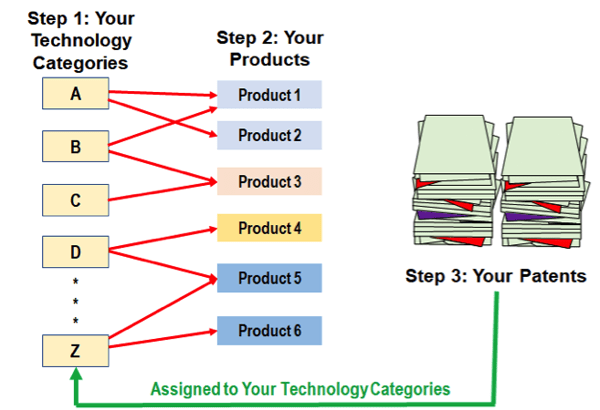

There are five steps involved in creating a Patent Rosetta Stone. The first three steps are all internal facing:

- Develop Technology Categories. The first step toward creating a Patent Rosetta Stone is to develop or use technology categories representing the various technologies that you have.Each company has a unique company culture and lexicon. This step takes advantage of that uniqueness to anchor the Patent Rosetta Stone in language that your company’s culture will quickly grasp.

- Map Technology Categories to Products. Some, perhaps many of the company’s products contain multiple technologies – consider an iPhone for example.

- Assign Patents to Technology Categories. If the company has many patents this can be a time consuming exercise requiring input from key technical experts and perhaps patent lawyers.

Once you have made these assignments you should be able to call up a product or product family and get a list of the patents that protect those products.

The fourth and fifth steps are the key to creating a useful Patent Rosetta Stone.

- Break Out Portfolio by CPC Codes. Take your patent portfolio and break it up by the Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) codes that have been assigned to each patent by the patent office. These are the codes used in patent prior art searching and examination by the patent office.

- Assign CPC Codes to Your Technology Categories. CPC codes are a standard coding system that knows nothing about how you describe your technologies. By assigning CPC codes to your unique Technology Categories (your “technical lexicon”), you have your completed Patent Rosetta Stone:

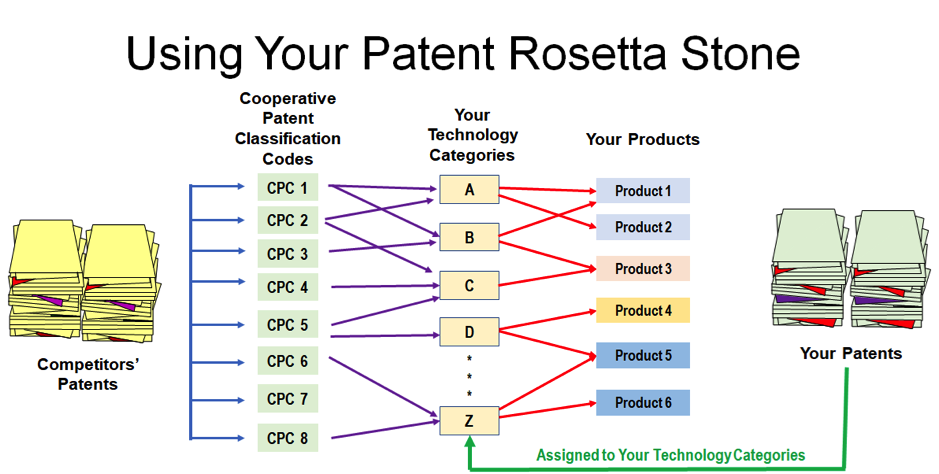

Using the Patent Rosetta Stone

With the Patent Rosetta Stone in place, you can now easily look at a competitor’s patent portfolio. You do this by sorting the competitor’s patents by their primary CPC Codes. Then, use Your Patent Rosetta Stone as a “translator” to align the competitor’s patents with your Technology Categories and through those to your Products:

You can also use your Patent Rosetta Stone to track emerging competitors and new technologies. On a periodic basis (weekly even), collect the newly published patent applications in the CPC Codes in your Patent Rosetta Stone, and “flow them through” your Technology Categories to your Products. Also, consider whether additional patent filings may be appropriate to stake claims in the newly emerging areas that are revealed through this process.

Stick with us through this series, because we'll keep sharing significant information that will help any Board member, but most particularly new Board members, evaluate their company's intellectual property. Up next, we'll evaluate your patenting process.