To this point, we have discussed the importance of IP and the high level questions a Board of Directors should ask Management. These questions cover a wide range, believe it or not. It’s never so simple as simply knowing which patents the company holds, though many Boards leave even that much to the IP lawyers. We started with the deep dive into research and development, with questions such as:

- Are we investing the appropriate amount in R&D, both in absolute terms and versus our peers? As we have shown, a key metric here is R&D as a % of revenue.

- How efficiently are we “harvesting” some of the value of that R&D by creating intellectual property in the form of patents?

- Do we know what technologies we have and how they relate to our products and strategies?

The next two high level questions a Board of Directors should ask are:

- How “good” are the patents the company is getting?

- How, specifically, do these patents add value to the company?

First, let’s explore the “how good” question. To do so, we’ll need to begin with a little background about patents. Let’s return to our earlier description of patents as real estate. One fundamental right you have when you own a parcel of real estate is to prevent trespassers from walking on or using your property. However, it’s important to note that this does not necessarily mean you have a right to use your real estate.

What? How could that be true? What would be the point of buying real estate, then? You’re starting to make our point for us, but let’s examine why.

If your parcel of real estate is “landlocked” because someone else owns all of the adjacent property, you have no way of reaching your parcel unless you and the other landowner reach an agreement to provide an easement.

So, what determines the boundaries of the real estate parcel? In actual real estate, we have the survey to mark the legal boundaries, and then we put up fences to keep others off our land. Strong fences obviously work better at deterring trespassers, right? The Great Wall of China didn’t keep the bad guys out forever, but it certainly held them off for a while.

Patent Claims as Fences

The strength of your patent “fence” depends on the quality of the patent claims. How clear is the language? How strong is it? Are terms vague, like a rotting cedar post fence? The Great Wall of China was built in the 7th Century BC and withstood trespassing attempts until 1878. If we compared the strength of that “fence” and my neighbor’s, which is currently falling over, to the strength of patent claims, which do you think would be more lucrative choice?

Sure, the Great Wall did eventually fall after nearly a thousand years of attacks, but the rotting fence is no deterrent at all.

How can we determine the strength of the “claims fence”? There are two basic questions: first, is the claim well written, does it clearly describe something? Second, what does it describe? IPVision Claims Analysis answers the first question using an expert system of claims interpretation rules from actual court cases and from IP licensing and litigation experts. We use the rules from these experts because unlike the patent prosecution lawyers who write patent claims and represent you in the Patent Office, the IP licensing and litigation experts see what makes a claim strong or weak when it is tested in actual business situations or court cases.

IPVision Claims Analysis examines each section of the independent claims of a US patent or application and generates over forty separate claims vectors. These claims vectors are analyzed using proprietary algorithms and rules provided by the experts and extracted from relevant court cases, ranging from simple measurements such as claim length to complex attributes such as preamble to claim ratio, number of occurrences of terms, and more.

There are a number of insights that come out of an IPVision Claims Analysis, but there are two key metrics:

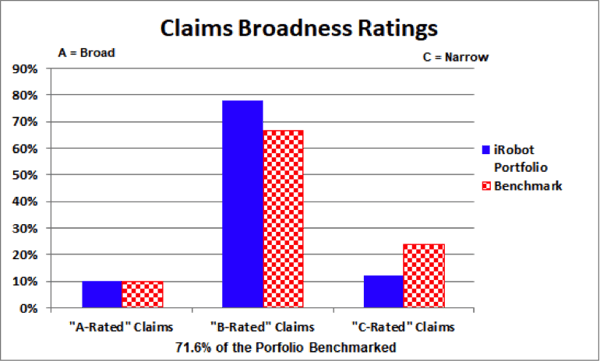

- How Broad is the Claim: Breadth/Scope Rating of A, B, C – where A means Broad Scope and C means Narrow

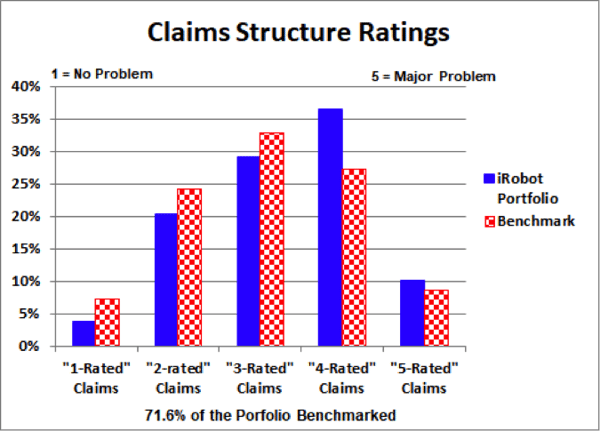

- How Well Written is the Claim: Structure Rating of 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5 – where 1 means no obvious language defect issues and 5 means a number of potential interpretation problems

What Claims Analysis Can Tell You

When you can see the quality of the Company’s patents you can ask questions such as:

- Which internal lawyer or which law firm is getting the Company the best patents?

- How does the Company’s claims quality stack up against others?

IPVision has a case study about the use of Claims Analysis to select and monitor patent law firm quality and patent spend. For example, if the quality of the patent claims of a patent application is decreasing during prosecution perhaps we should not continue to spend money on that application.

Claims Benchmarking

How do the claims of the company’s patents stack up again the claims of their peer patents? A "peer patent" is a patent (a) in the same technology area and (b) granted during the same time period as the patent in question.

These two criteria are crucial because when a technology is “new” there is more “land” to claim. As the technology matures the opportunity for broad claims decreases and the narrowing of claim language introduces more opportunity for structural issues to arise which makes it harder to interpret and enforce the claims.

IPVision Claims Benchmarking can be done on a company’s entire portfolio or a technology or product area. Here is an example of Claims Benchmarking for iRobot.

Example: iRobot

In this example, we benchmarked the claims of US patents in the top five Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) System Technology Subclasses in the iRobot portfolio over what was at that point the previous 10 years. These patents comprised 71.6% of all the US patents in the portfolio (341 patents and 739 independent claims).

The Benchmark consisted of 24,957 US patents in the five CPC Subclasses and in the same timeframe. These patents have 59,625 independent claims. The Broadness and Structure comparisons are shown in the following charts:

The Claims Broadness Ratings for the iRobot Portfolio benchmarked is slightly better than the benchmark, with A-Rated claims being in line and B-Rated claims being about 11% points better in the iRobot portfolio.

The Claims Structure Ratings shows that the iRobot Portfolio Benchmarked has significantly fewer “no problem” claims and significantly more “4-Rated problem” claims than the Benchmark.

Conclusion: this “first pass” analysis suggests that the patents in the iRobot Portfolio could be overall somewhat “weaker” than their peer patents from an enforceability or licensability viewpoint. There is a caveat: further analysis is required in order to determine the relationship between these weaker patents and the major revenue and profitability components of iRobot’s business.

We'll continue this deep dive next week, as we discuss time horizons so that Boards of Directors can discover realistic expectations for IP development.